The Tornado Killer

The year was 2006. A young meteorology student named Paul sat musing in one of his university's several libraries. Here at the university, he and his fellow students were bombarded daily with all manner of informational media. The university provided free newspapers to all students. On the walls of the lounges in the big student union building there were large flat-screen televisions, constantly showing national newscasts interspersed with educational programming. The internet was everywhere, as students walked from class to class staring at their mobile devices, or sat with laptops in front of them, seemingly constantly. And of course, there were classes, the reason they were all here.

Today, Paul had pieced together some large chunks of the information with which he had been provided. There was a worldwide energy crisis, that much was indisputable. One of the more intriguing energy projects he had seen involved the actual construction of chimney-effect generators. They were nothing new, but had recently been re-investigated. Some were actually operating elsewhere in the world, others were under construction. A large generator at the base of a tower-like chimney is driven by updrafts, as warm air at the surface is drawn up through the chimney into the cooler air above.

Enter the meteorological part of the problem. Tornadoes appeared to Paul to be the equivalent of an uncontained rush of warmer surface air to the cooler air of the upper atmosphere. An internet search tended to confirm that suspicion – tornadic activity is the result of powerful updrafts and wind shear, fueled by the temperature and moisture differences between cold air from the Rocky Mountains and warmer surface air in the plains to the east. Although it obviously wasn't that simple, the fundamental facts appeared to be irrefutable.

It didn't take much imagination to see the apparent symbiotic advantage to generating power in the midwest, or along a line between the Rockies and the midwestern United States. Air would be warmed in the upper atmosphere by the generation of power using the chimney effect, and the tendency of the temperature differential to create tornadoes would be diminished, perhaps enough to prevent destruction of lives and property in the so-called “Tornado Alley” and elsewhere in the U.S.

It seemed to Paul like a sound idea, and with benefits like it might well produce, what could be lost by telling someone? Paul decided to go and talk to his adviser, an accomplished meteorologist whose specialty was the study of tornadoes.

Paul's adviser was an open-minded scientist, an associate professor who wasn't anywhere near achieving tenure with the university. It was his first faculty position since having completed his own postdoctoral work. He sat quietly for a minute and gazed at this seemingly presumptuous, completely inexperienced undergraduate student. Here was an opportunity to involve himself and his students with something new. He understood the grand scale of the natural forces involved, and that they spanned a continent in this case. It also appeared that the relatively small amounts of air that would be displaced would have little, if any effect on tornadic activity, but there was nothing to be lost in conducting some research into the matter. There was the irrefutable fact that powerful updrafts were occurring. If one took into account the interdisciplinary efforts being made increasingly throughout the sciences, the effort to provide power without carbon emissions alone was a powerful draw. Surely it would be possible to interest the National Science Foundation enough to gain some funding.

“Let me have a couple of days to see our department head,” the professor replied to Paul. “I see what you're trying to accomplish, and it sounds pretty awesome. But I want to see what my superiors think of it, before asking for the go-ahead to apply for any research funding. You do understand this would have to be a completed research project before it could capture the interest of some agency or corporation who would actually try building even one of these stacks, don't you?”

Paul grinned and nodded. This was awesome. It was the way innovation was supposed to take place, and he would be a part of it.

Paul walked toward the bus stop, thinking. He didn't want the idea taken from him by an interested superior, never mind that it was his academic adviser. The best way he could think of to circumvent the possibility was to tell other students about it. He turned back to the student union building, and called some friends on his cell phone.

Soon a little group of four converged on the coffee shop of the student union building. It was a scene that is repeated frequently on college campuses, nationwide. Intelligent young men and women discuss ideas to improve their own future, oblivious to the negatives, shortcomings and downsides. As the outlook is positive, generally the outcome is also positive. If anyone could ever track the outcomes, the list of ideas generated thus that become reality, would be a very long list indeed. Among the issues that are coming of age as this is written, are proven means of active carbon sequestration, innovative methods of secondary oil recovery from “expended” oil fields, a new and effective way of scaling up a means of extracting electrical energy form biological wastes, and the list goes on and on, in all of the disciplines of the sciences and of engineering. It is a big part of America's technological edge.

At first Paul's idea was received a little incredulously. “You wanna what?” one of his fellows queried.

“Think about it!” Paul responded. “Tornadoes aren't going away. That means at least one of two things. Either we need to find a way to make them go away, or there's at least a carbon-free source of inexhaustible energy, right there in the heartland of the United States! And wouldn't it be something if we could accomplish the one with the other?”

And they did all think about it. Sixteen cups of coffee were purchased at that one table, that afternoon. Classes were missed. But the more they thought, the more plausible it seemed. After all, one of them believed the greatest thing ever would be to terra-form the planet Mars. What could be more grand than to make an entire planet livable, opening it up for colonization by humans? In such a project, an entire planetary atmosphere would have to be generated and retained.

By comparison, modifying weather patterns to mitigate the tornado problem seemed pretty miniscule. “Okay let's do it,” one of them said.

Just like that.

The next morning, before Paul's adviser had even gotten to see the department head, the group converged on his smallish office. The morning sun streamed in through the window and the heater beneath it droned. Four undergraduate meteorology students talked excitedly about the possibilities.

“Okay, okay!” The professor chuckled. “I'm scheduled to see Bill this afternoon. There are some other things that come first on the agenda, but this won't be left out. Give me a chance to see what he thinks.”

Well, “Bill” thought it was great. “The most important thing you can do, in my estimation, is to encourage innovative thought in your students,” he said. “Good job! Yes, you will want to get in contact with NSF, and let our contacts at NOAA hear what you're thinking of doing. Make it clear in your proposal that research requires support, and that you are specifically asking for it. Then let me review the proposal before you hand it over to the research office.”

Years passed. Grants were forthcoming from the National Science Foundation, then from an energy-producing company, and when some momentum had been reached, a series of grants came from several state governments in the midwest. Soon the figures were assembled and a federal grant was added to the energy-producer's construction project for a 200-foot tall chimney-effect generator near Tulsa, Oklahoma. Unlike the operating towers in Spain and Germany, the American tower did not require wide areas of solar collection to pre-heat the air, rather, they needed to be able to throttle back the tremendous draft created in the chimney. The generator obviously needed to be increased in size and output.

Based on the figures in terms of megawatts produced, the chimneys soon started popping up all over the midwest. And even more significantly, the dream of mitigating the tornado problem was apparently becoming reality. Of course, the continental size of the air masses involved, and the less-than-dependable nature of weather patterns did not eliminate the threat altogether. But now, scientists were in the frame of mind to believe they could do something about it.

Paul himself came up with the idea of the air bomb. Formation of a cell brought a quick response from a rocket tipped with a device that had been previously known as “the poor man's nuclear weapon.” There was nothing at all nuclear about it, but the resultant burst, usually at about 10,000 feet, warmed the air at altitude enough to reduce that particular updraft to zero, right away. The downside? Sometimes, it took two of them.

In the year 2012, a farmer named Everett worked on his fences on a comparatively small farm several miles southwest of Harveyville, Kansas. His childhood had been interrupted by the total destruction of his father's farm buildings by tornadoes in Oklahoma. The farm had to be sold, and he'd been brought up in suburban Tulsa because that was where his father had found work.

Here in Kansas, Everett had decided to make a new start in farming. Some of the money inherited from the sale of his father's farm was still available, and he had placed everything on the line. Everett worked hard and had every reason to believe he could make it. This farm wasn't particularly large, but the agricultural community had welcomed him, and it was obvious the people here wanted him to succeed. Midwestern people are a little different. Here the values that built the nation still prevail, and if cooperative help could be found anywhere in the country, this was the place.

Everett looked just to his west and his eyes followed the contour of the huge stack, widening at the base to a bell-shape. He had heard the pitch of the generator change slightly. It was a soft sound that was always there, a lot like the sounds of the windmills that had once moved most of the well water here in the midwest. But it was a really small price to pay for not having to worry about tornadoes, anymore. Everett went back to work.

But as we all know, that didn't occur in 2012, and perhaps won't at all.

Here is what really happened.

A young farmer gazed at the developing thunderhead in the western sky. Out here in the expansive, flat farmlands of Kansas, one could watch storm activity occurring many miles away, and yet never get a drop of rain. Usually a distant storm would come and go without so much as a dark cloud blocking the sun where you stood. You could easily see it, if the affected area was getting any rain.

This thunderhead, however, was close, and it was looking pretty ominous. Tall and rising in height with a darkened underbelly, it had the look of the makings of tornadoes, and it sent a shiver down the young man's back. He could see lightning high up in the clouds, and there was obviously already some precipitation coming down somewhere, not far away. He wondered if it included hailstones, a common occurrence with a storm like this one.

The farmer's name was Everett, and he knew something about this because he'd lived through it before. Everett had been raised in Oklahoma on a large farm, and a group of small but violent and fast-moving tornadoes had devastated all of the buildings on it, including the family farmhouse. Because the tornadoes had swept through near the middle of the day, everyone had been close enough to the house to make it to the storm cellar, and they had all survived. But the total loss of buildings and livestock had been too costly to allow his father to continue. His father had sold the farm and had moved the family into Tulsa. The rest of Everett's boyhood had been spent in a suburban rental home, and their father had found work in a dairy processing plant there.

Everett had worked his heart out to get back to the land, and now that he was here, he was determined to make it work. This farm wasn't particularly large, but the agricultural community had welcomed him, and it was obvious the people here wanted him to succeed. Midwestern people are a little different. Here the values that built the nation still prevail, and if cooperative help could be found anywhere in the country, this was the place.

Up until now, Everett had been fixing fences about a half-mile from the house and barn. He decided to head back. He collected the tools he'd had out of the old Chevy pickup, started it up and wheeled it around to return to the house.

Everett was about two-thirds of the way back to the house when he saw the first funnel cloud start to form. It was long and gray, and the end appeared to whip from side to side like a snake. When it touched down, Everett knew it because it quickly turned dark. That was because of the dirt it was picking up, which would immediately be joined by debris from the things the violent twister was destroying, or uprooting.

Today, everyone in the general area where the tornadoes formed would be lucky. Tornadoes are a natural occurrence, and despite the freakish things they have been known to do, in fact they can come down anywhere at any time of the day or night. They do not deliberately touch down to destroy anything, they just happen, do unbelievable amounts of damage, and then disappear.

Everett and his wife and little daughter felt particularly fortunate, because they were able to watch the funnel clouds to either side of their farm as they proceeded past. By about 2 p.m., the danger seemed over, and they decided to get some lunch before Everett would get back to work.

Over lunch, Everett and his wife Ellen discussed what they had just seen. To this point they had not invested in insurance that covered loss to tornadoes, because of the expense. But how much more would it cost them if they had a loss?

Regardless of where they are located, American farmers have to struggle with fuel and equipment costs like everyone else, but they are powerless to simply raise the price of their commodities to cover increased costs. Under-appreciated and overworked, they do what they do for the love of it. There is no other explanation. They choose the way of life, and fortunately for all of us, they don't go on strike just because times get hard.

Although they weren't certain where the money would be coming from, Ellen and Everett agreed that they'd better try to find it. Everett would drive into town and withdraw enough for a first premium payment, and get the policy in place.

At the same time in the eastern part of the United States, another young man was sitting at a study table in one of the libraries, thinking. Here at the university, he and his fellow students were bombarded with all manner of informational media, daily. The university provided free newspapers. On the walls of the lounges of the big student union building there were large flat-screen televisions, constantly showing national newscasts interspersed with educational programming. The internet was everywhere, as students walked from class to class staring at their mobile devices, or sat with laptops in front of them, seemingly constantly. And of course, there were classes, the reason they were all here.

But it didn't seem to matter what new ideas were inspired by all of that information. There was only one thing that made anything happen, and that was the flow of money, or the imminent promise of it. Further, it wasn't enough to have a great idea. You had to sell it. But even more, you had to be in a position to sell it. And students, were not.

Paul had just had a great idea. He was a meteorology student, but an undergraduate. That meant he had years to go before he could even be considered for post-graduate work, and if he measured up grade-wise, it would be many more years before he might hope to secure a research grant of his own. And then, there was the problem of actually developing something out of that research that would result in something tangible to solve a problem. If you could show that it had a chance to work, that wouldn't be good enough to build a prototype. Because it would take money.

If Paul had learned anything during his first three years of college, that was likely the most impressive thing he had learned. Money runs everything, and its flow is controlled by people who are only interested in making more of it. In a way it made sense, but in another way, it seemed preventive of progress, counter-productive. Paul would be a scientist, not a financial wizard. His career that would be dogged by a lack of funding was just on the horizon. In fact it is a dirty little secret at major research universities like this one, that professors received tenure if, and only if, they were also financially-minded enough to pull in big-dollar research grants that would benefit their department, and thereby, the university. Ha. And some people thought it was about football!

It didn't take much imagination to see the apparent symbiotic advantage to generating power in the midwest, or along a line between the Rockies and the midwest. Air would be warmed in the upper atmosphere by the generation of power using the chimney effect, and the tendency of the temperature differential to create tornadoes would be diminished, perhaps enough to prevent destruction of lives and property in the so-called “Tornado Alley” and elsewhere.

In spite of what Paul had learned about the way that money works, it seemed like a sound idea, and with benefits like it might well produce, what could be lost by telling someone? Paul decided to go and talk to his adviser, an accomplished meteorologist whose specialty was the study of tornadoes.

Alas, Paul's adviser was a scientist only, and he was also a young professor without tenure. He would not likely be making a mark here. Furthermore, he was negative about any such venture.

“You don't understand the scale of these events.” the professor asserted. “These are continent-spanning air masses, unpredictable and massive beyond your imagination. And besides, you would have to construct towers tall enough to get the air ten thousand feet up, at the very least, to reach the cold air that's in question.”

“But I don't understand,” Paul replied. “The very fact that tornadoes span that distance seems to suggest that there is no barrier between the colder air mass and the earth to prevent the warmer air from rising higher. We can build huge cooling towers for nuclear power plants, why can't we build a lot of taller, narrower chimneys to harness the differential, maybe three hundred feet or even less, and in the process, conduct the warmer air in a controlled fashion such that the air moves higher by virtue of its velocity and temperature? Even if it didn't succeed in stopping tornadoes from forming, the huge updrafts that we already know occur in the area would pay for the project through generation of electrical energy!”

“Enough,” his adviser snapped. “When you've put the time and effort that I have into study of the tornado phenomena, you might begin to understand. I've got a class in fifteen minutes.”

Paul got up and left without another word. He had just presented a sound argument to a man whose mind would not be changed by the facts. Throughout human history, progress of all kinds has been hampered by the sort. So impressed was the professor by the immensity of the weather systems that created tornadoes, that he considered them to be majestic, awesome, amazing. They were not to be controlled or eliminated, only predicted. Paul wondered how the man would feel about it if a tornado had destroyed his home.

Many people might have urged Paul to keep trying, to complete his degree and then to apply for graduate school with the longer-term goal of realizing his dream. But no one else was present to express it. From a personal standpoint, Paul was practical enough to understand that the odds were against his progress in this particular area. He decided to realign his priorities to those of his department head, who was actively involved in tropospheric research. There was funding available for study of the upper-atmosphere aerosols that affect the ozone layer, and thereby, global warming.

The tornado killer had been killed before his own birth, by a closed mind at a major university.

Back in Kansas, Everett had just completed his trip to town and had gotten his insurance policy to protect his investment. He felt a little better, although the cost was something he was certainly worried about. The only way he would make it work would be if prices stayed where they were or increased, and if crops came in as expected. Now there was no margin for any additional problems. But destruction like he had experienced on his father's farm as a boy would have been certain death to his own effort to maintain a farm. It was almost a “damned if you do, damned if you don't” scenario.

Later that night, the weather system that had swept through the area happened all over again, this time, in darkness. And this time, Everett wasn't nearly so fortunate. In fact, the onslaught came so suddenly that none of them made it to the storm cellar. Everett regained consciousness when it was over. He was still within what was left of his house, and was extricated from the rubble by neighbors the following morning, and was rushed to a hospital some forty miles away. His wife and daughter were not in the house. Their bodies were discovered, later that day.

Although tornado insurance might have been enough to allow Everett to continue farming, he found he no longer had the desire. He blamed himself, why hadn't once been enough? If he hadn't insisted on returning to farming, maybe he would still have a family.

Tell that to the people who lost family members in the nearby town.

*********************

Finally finished. Great use of a unique format, I'll probably steal it myself someday

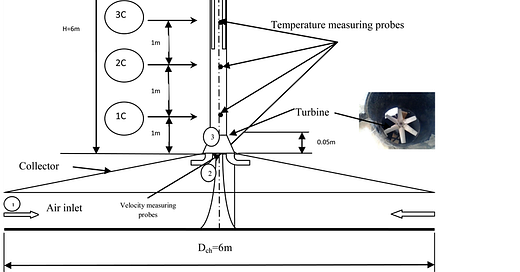

Only half done so far, but my first thoughts: is the "velocity probe" like a Pitot tube? Or a really fat Venturi? My immediate concern with a chimney generator (having done exactly zero research) is condensation as the working air rises, cools, and drops in pressure. Sure, mechanical moisture separators are an option, but that much headloss in a system with an already small pressure differential? I can imagine a system of condensate drains, but not one that would both be easily maintained and cost less than the ISS. I would also worry about frequency control, assuming an AC generator, but I'm sure there's an electrical engineer somewhere who's already cooked up a solution to that one.