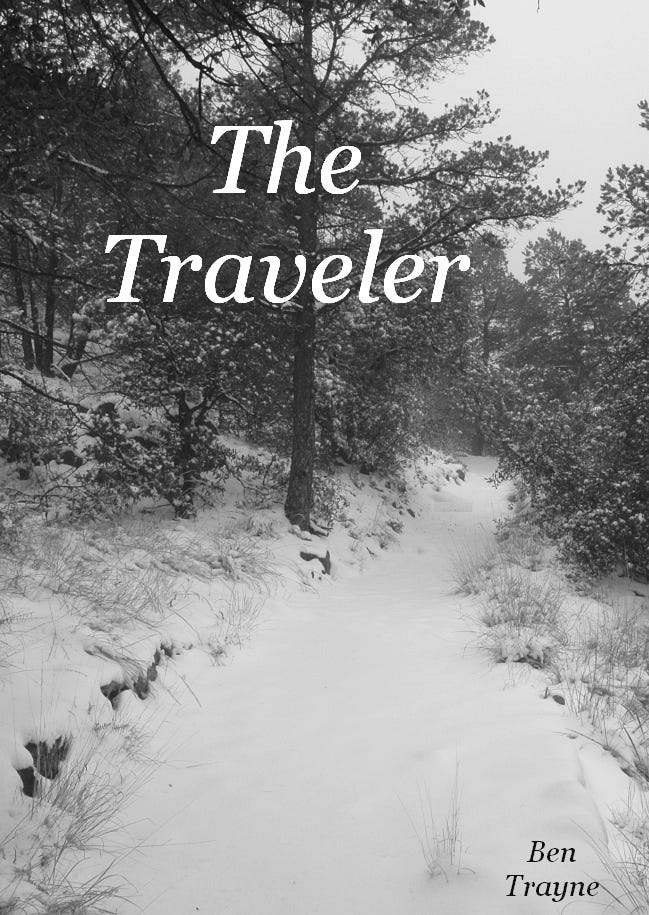

The Traveler

A lone figure clad all in gray, a nameless, ancient and solitary traveler, solemnly made his way through an unlikely wilderness. In an untrodden, heavily-forested area of the rock-strewn hills of rural Pennsylvania, the advancing, slightly bobbing form blended ethereally with the bare and desolate trees through which he slowly moved. Gray he was, in every way and everywhere, save for the tawny color of his footwear and the aged pale tint of leathery skin. Very little of that had been left exposed to the bitter February cold. He stabilized every other step with a stout gray staff, long his companion. The weathered grayness of the staff had been well-earned over decades of foot travel, the bottom end worn round, the grain of the wood hardened from use. The gray head was topped with a tall, but crumpled and broad-brimmed hat, a too-perfect match with the shade of his cloak and his long, full beard. The bottom edge of the cloak left its own trail in the several inches of soft new snow that covered everything, for hundreds of miles about. Noiselessly he moved, a well-practiced and effortless stride, on moccasined feet.

For a moment the old man stopped, tipped his head back and gazed upward through a patterned artwork of leafless branches, into a pewter sky. His eyes closed and his lips moved, but his words were given no voice. Then he moved on, still in silence.

Many miles away and moving on an eventual intersecting path, a not-so-silent train of loaded freight cars clacked individually but rumbled in unison, winding their own way through the wintry wooded countryside on confining rails. A back-to-back pair of diesel locomotives drew them, emitting their own synchronized grumble, as if they were one.

Deep within the pitch-blackness of the oil sump in one of the sixteen-cylinder supercharged diesel engines, a miniscule, jagged speck of granite-hard steel tumbled randomly in the churning, seething lubricant. One moment it rose in oily froth, in another it fell, driven downward by another current in the dense, hot fluid. The thrusting connecting rods pounded in and out of the oil, and the great forged crankshaft spun relentlessly.

The contaminated engine was within the second of the two huge dusky-brown locomotives. Both had already been throttled-up to deliver two-thirds of the their combined nine-thousand horsepower capability, but the matched pair had begun to struggle in pulling the seemingly endless train of heavily-loaded freight cars; they struggled because the heaviest segment of rusted hoppers, fully weighted with freshly-stripped coal, had just begun ascending an increasingly insistent grade. It didn't help that the total load calculation was lower than the real number, and that there were a few more cars than a pair of engines could haul with best efficiency. But the engines were both in top condition, outfitted with the latest controls and attended by two capable engineers. The controls limited the train's speed, and helped to adjust the output of the engines to suit whatever load would be encountered.

And at that moment, those controls were coaxing the two big diesels to full throttle.

Of course, most engines have an oil filtration system. However not every drop of lubricant necessarily passes through it. Deep in the darkness of the sump are pickup points from which the oil is drawn and fed to the lubricating pumps. When the acceleration is sudden and substantial, the restriction of the filters causes a bypass valve to open. Thus, an adequate amount of oil can be delivered.

Now, just such an acceleration was occurring. The superchargers wound up, the deep thrum of the diesels now roared and increased in pitch, more fuel was drawn into the injection system, exhaust doubled in volume and velocity, and the formerly harmless shard of metal was pulled into the highly pressurized flow of the mighty engine's oiling system.

It happened at the precise moment the solitary traveler looked skyward and spoke, soundlessly.

The lead engineer really loved his job. Inspired by the burst of power from the great machines, he reached up and pulled the lanyard, releasing a long, five-toned burst from the airhorns. A harmonious, if not unsettling, blast of thunderous train music rolled away across the pastoral valley floor. Some of it echoed back from the more mountainous region they were about to enter.

In a modest home some miles ahead, a hard-working young mother named Carey hurried about, preparing to transport her two young children to her mother's home. Grateful she was to have a job anywhere in the local economy, but she also hated the daily separation from her infant son and four-year-old daughter. Seven years earlier she had married the love of her life; less than a year ago he'd been killed in a tragic accident. They didn't have a lot of insurance. Now she was alone, struggling to keep her home and to feed her children. Carey hadn't had the opportunity to attend college, and she realized her children would now likely be raised in poverty. At least, she reasoned, her kids might build character because of it.

Of course, she was right. In fact she had no idea how right she was. Her daughter would become a great economist, the sort that can craft solutions for a flawed, poorly-conceived monetary system. Her son would be nothing less, brought up with little to eat and less to hope for. He would succeed against all odds and then rise to power at a critical time, leading a world to safety and prosperity at long last, through the reins to a nation.

Or perhaps the terms should be "would have become" and "would have been".

Carey finished bundling her children to make the short trip, then stopped, smiled and touched the lips of her infant son with one finger. He smiled back, a radiant and endearing smile. No childless person, possibly no man, could ever grasp how she felt.

The gray-clad traveler finally stepped out of the thick trees of the forest and detoured around a thicket of tangled young grapevines and spiny hawthorn. The area he had just entered had been timbered a decade earlier and was overgrown with redbrush, and also well-populated with white-tailed deer that subsisted on its abundant browse. He selected a trail the deer had made through it, thus varying little from his original, purposeful path.

Near a crossing of deer trails within the redbrush, a poacher was crouched. He'd heard nothing at all before the gray man appeared, and he still heard nothing, as this odd fellow approached. Each was in plain sight of the other, but the man in gray never so much as turned his head to look. The poacher placed his silencer-equipped weapon on the ground and rose, gaping at the stranger as he strode by in total silence, working his staff in steady cadence. Even the staff made no noise as it contacted the earth. The stranger's aloof passage made it seem as though he, the poacher, didn't even exist. How quietly the gray man moved! Suddenly, it struck him that the wraith-like figure might not even be real; and he feared for his life and his sanity.

He'd seen people before who lived in these hills, strange people who never came down for groceries, who lived without electric power and who were unknown to the government. There were no roads for vehicles, so they had none. It wasn't wise to approach any of them. But for some inexplicable reason, he knew this man was not one of them...if he was anyone at all! Without thought, the poacher abandoned his weapon and began to follow the gray one at a distance, half-expecting him to vanish at any moment, and sincerely hoping he would not.

By this time, the approaching freight train had cleared the height of the grade. The errant shard of steel had reached its stopping point within an oil groove of an bronze sleeve, which served as bearing and guide for the exhaust valve atop cylinder number six. There the shard had become doubled-over and had embedded itself in the wall of the sleeve, and was busily galling itself to the rapidly-moving valve stem. Thus the critical valve had already begun to stick for a moment, with each sliding movement to open or close.

Within a matter of ten minutes, the valve had seized entirely, lodging firmly in the "open" position, which meant it was in the way of the piston. Piston number six plowed into the valve repeatedly at an extreme rate, the sturdy valve stem bending twice and becoming thoroughly wedged in place. Fuel continued to be injected, but with the valve open, no compression could develop to permit its function. Though the piston continued to move, the cylinder was dead.

The catastrophic sounds produced by the engine's internal wreck were inaudible to the engineer from within his cab. What he did hear, and feel, was the sudden drop in engine speed, the vibration from an unbalanced series of combustions and the clear misfiring of the big diesel. Immediately the entire train slowed. The engineer jumped to survey the gauges, and noted only that fuel pressure had become unbalanced. Then he glanced up through the windshield and saw the heavy black smoke from unburnt fuel passing through the hot exhaust manifolds and into the air. He had seen coal-burning steam locomotives operate, and they never made smoke as thick or as black as this. He opened up the com channel with the lead engineer.

"Hey Buzz, got a problem..."

"Yeah I know. I can see it and feel it."

"What do we do?"

"You know as well as I do. I'll call, but they're gonna tell us to bring it in. We power up the other loco and give it hell, and hope we make it."

"Are we gonna shut this one down?"

"Nah. Wish we could break it loose, kick it out of gear! These babies don't have gears. Let it run as long as it will, it'll lessen the drag on the Queen Mary, here."

"Buzz!"

"What?'

"Think we'll make it?"

The lead engineer paused. "Yeah, I think so. Hope so."

Young mother Carey had strapped her children into their car seats and had started the car. At least, the silver-gray, ten-year-old Buick was in good condition. As they lived miles out of town, she depended on it for just about everything; work, groceries, and soon enough, school. It would be about an eight minute drive to her mother's home once she reached the main road. Carey backed the car around and headed it down the long lane, toward the railroad crossing.

A freight train as long and as heavy as the one headed Carey's way would ordinarily require a mile and a half to stop. The locomotive's traction motors can be reversed and used as brakes. Without the assistance of the traction motors of the second engine, this train would require more.

But that would be if it was running at speed, and it was not. The further it went, the more the telling drag of the injured, smoke-belching diesel took its toll. The speed limiters usually held a level-moving train at fifty miles an hour, but it soon had dropped to forty-five, then seemed to hold for a while, at forty. "We'll make it in," the lead engineer asserted over the com. "I'm sure of it. We've no more grades to climb on this route, and the "Queen" is a strong lady. We're over halfway already." He nudged the manual throttle, and the speed of the train increased slightly. Nevertheless, in the injured engine, the gathering of fuel in the manifold to the injectors had begun to bog the other cylinders, and the density of the black smoke continued to increase. It poured relentlessly from the engine's exhaust stack.

The gray traveler, having passed through snow-covered fields, had finally reached the top of a high bank that overlooked the railroad tracks. Across the way and from an equally high bank, Carey, driving the Buick, now also approached the tracks. From the distance she saw his gray form, his staff, and the tipped gray hat. What a strange-looking man. Why was he there? But as usual, she slowed very little as she proceeded down the road and onto the steeper incline that led to the tracks, and to the main road just beyond. She had completely forgotten to take into account the several inches of damp snow that still lay undisturbed on the secondary road. Her family was one of only three that used the road, and the township had never considered clearing it as a priority. It was no different this day. The only stop sign was on the other side of the tracks, and usually, she simply drove right on across them without slowing.

But as the Buick started down the steep incline, she realized her error. The steering had already failed to respond, the tires almost tractionless on the snow. Instinctively she mashed the brake pedal and locked up the wheels, and the mid-sized automobile immediately rotated about the left front tire, simply because it had the best grip of the four. The car began its inevitable slide, canted at a fifty-degree angle to the centerline of the road at thirty-five miles an hour. The traveler stepped from the top of the bank and began to take long strides toward the car. He had taken no more than five of them when the left front wheel of Carey's automobile thudded into the first rail, just off of the paved section that had always allowed her to pass over both rails without damage. The inertia of the Buick forced the tail end of the car to slide out another thirty degrees. The back wheels bumped over the rails and the Buick stopped, positioned squarely across the tracks, half-on and half-off of the elevated pavement between them. Frightened and flustered, she pushed the car door open and prepared herself to see how badly the car had been damaged. The left front wheel was bent sharply inward from the strike against the rail, and it appeared the suspension was buckled under, as well. "Oh, no," she wailed.

Once it made the next curve, the freight train would be approaching Carey's crossing. The road was little more than a driveway from the fields, and engineer Buzz had never seen a vehicle there. But in good caution and pursuant to his training, he tugged the lanyard four times, releasing two long blasts, a short and another long. Just as he did, a flash reflected from the windshield and he felt an explosion from behind. Whirling quickly about, he peered through both cabs, looking past his fellow engineer. Flames leaped from every opening in the steel cowl above the diesel, and that definitely constituted an emergency. He turned back around, reached forward and forcefully applied the automatic brake, slamming it home. Then, he reached for one of the big fire extinguishers with one hand, for the radio mike with the other.

No one's terror has ever exceeded what Carey felt when the oncoming blare of the freight train's horns pierced the February chill. So terrified she was that she was beyond making sounds of any kind. She scrambled to get her children out of the car, but at the nearly paralyzing level of fright that now held her in its icy grip, she could barely move her fingers to undo the buckles. Both children were securely snapped into protective child seats; and failing to simply unsnap the first buckle, she turned her attention to releasing her daughter's seat, because it was the nearest, from the belt system that secured it. It had been too long since the seat had been fastened-in, the belts were pulled tightly into the space between the seat back and seat bench, probably by her husband. Carey had to know! She turned her head and shoulders and gazed quickly down the tracks, and she saw the oncoming engine at the same moment the engineer saw the car. It helped not at all that he pulled the lanyard repeatedly, its powerful bursts proclaiming the imminent death of Carey and her children, acoustically shattering her final bit of nerve. If she could have moved, she would have. She didn't know that the train's braking system had already been applied, but in fact it scarcely mattered. Only a quarter-mile of steel rails remained between the front of the locomotive and Carey's car, and the train needed most of another mile to stop. The engineer was only trying to get any people to clear away from the obviously disabled vehicle, for completely certain he was, it would be crushed.

At that moment, the gray-clad figure had just reached Carey's side. Time was extremely short, as more than a thousand tons on steel wheels rolled inexorably toward them. At a speed that defied his apparent age, he quickly released the children from their safety bindings and scooped up the infant. Bewildered, Carey picked up her daughter. "Go quickly!!" He ushered her around the car and placed her little son on her other arm. "Quickly!" She did her best to run, knowing that her car was about to be hammered into nothingness by the oncoming freight. But it didn't matter now; her children were safe.

The lead engineer stared wide-eyed at the vehicle upon which the locomotive was rapidly closing. He didn't want to look at the speed indicator; he didn't want to know. He had reversed the traction motors, realizing it would be of little help with that much weight behind them. He saw nothing of what had occurred at Carey's car, or perhaps he didn't notice. There was only the coming impact, and he dreaded it. He shouted, "We're gonna hit it!" without even realizing that he couldn't be heard. He closed his eyes, braced himself against the control panel and waited. He had no wish to watch.

The gray traveler picked up his staff and stepped out onto the tracks. The flames about the second big diesel had already died, a phenomenon called "flashover" had done something strange to the generator, and the big steel wheels of the disabled engine were now grinding against the rails in reverse, as were the similar wheels of the "Queen". A miracle was in process.

In order from front to back, the brakes of each heavy car tightened, every wheel locked, and the slack that built toward the far end of the train soon had the last cars slamming into their couplings. The poacher who had followed the gray figure was now perched at the top of the bank, and as he and Cary watched from opposite sides, the very laws of physics were being defied. The gouging of steel rails that was occurring was not possible. Even that phenomenon should not have stopped the great train in such a short distance. Fire flew from the rails and wheels screeched, the sound raising to a wail that topped the former blast of five horns. Carey's eyes welled with tears. The gray man had spread his feet apart and stood with arms and staff raised, as if commanding the huge machine to stop. And when it did, when he turned to walk back to Cary and her children, she saw, only for a moment, luminescence of a garment of brilliant white. It shone from between the lapels of the gray one's cloak, explaining what had just occurred. Carey gently stood her daughter onto her own feet, and cuddled her infant son.

As he approached, she tried to speak. She wanted to say, "Who are you," but no sounds issued forth.

"Shh-shh. Don't worry. You're safe now. Let's get you back into your car."

"But - my car..."

"...is fine. You'll see."

With that, the stranger laid his staff aside, walked easily to the car and climbed inside. He drove it out if its predicament and pulled it up beside Cary and her children. She now stood right beside the left front wheel, which no longer appeared to be damaged. Now, she thought she understood. And with that, she at last found her voice. "My children are safe! But why did you save my car??"

"You depend on it, don't you? Besides, if you have the car, it will be that much easier for you to forget what you've seen."

"But, I don't want to forget..."

"Shush, now. You sound like a child. You can't be one of those anymore. You have these two to think about. And you won't forget everything; not unless you speak of it. I need you to load your family back in your car, and drive to your mother's home. You'll be five minutes late, let's not let it become ten."

"I was right! I did see white..."

"And the more you speak of it, the less you will recall! Please listen."

Carey nodded, and tears streamed down her cheeks as she at last smiled.

"Are you...an..."

"A guardian. Nothing more."

"Just one more thing! That voice! You sound, exactly like..."

"Yes! You even look like him!

The gray man laughed, heartily. "I love his voice. I love his performances. Others merely act, he performs. They are mere actors, he is an ac-tor!" Then he grew more serious, and placed a hand on her shoulder. "You will have questions, " he asserted, "and this is will be my one effort to address them directly. Pay attention."

"Your children are special, even more than you already believed. You must raise them as you had planned. Never be ashamed of poverty, it is nothing to be ashamed of. Your daughter and your son will know what it is, and that much is necessary. Please take my word for that. A wise man once said," he smiled, " 'And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.' I should like to add one. It is co-operation. Teach your children this! And, despite your cash condition, we cannot have you starving." He reached into an inside pocket and extracted a small, flat leather purse; as he did so, Carey caught another glimpse of brilliant white. He nearly whispered as he continued; "Never open this purse unless you are very much in need and have not been able to find what you need through honest work, and genuine effort. If indeed you have exhausted all of your options, then you should check it. It may not contain what you want. It may, however, contain what you need. Never speak of it. Keep it in a very safe place." Then, observing her apparent disbelief, he added, "There were two reasons to be here. One was to advise you to be much more careful! I might have stopped your car, but what would that have shown you? The other, my dear, was to give you that purse."

Carey still looked quizzical.

"Might I ask you one question?"

"Of course."

"If you could help us, why couldn't you ...well...my husband... those children..."

"That's not so difficult. Peace, harmony and even life itself, are dependent on behavior. Behavior is dependent upon what one believes. Perhaps a train can be stopped, maybe even a rocket, or a hail of bullets. But I am not permitted to interfere with free will. Otherwise," he said, looking into the distance, "It's not life. You have an opportunity to be free. Even though you cause one another not to be." He paused and looked into Carey's eyes. "Good enough?"

She nodded quickly, and smiled.

The gray man turned toward the poacher and spoke, in a much bolder and louder baritone; "You! Poaching my deer! No more!" Then he turned back toward Carey. "I must be on my way. And so must you."

"Where will you go?"

"I thought, while I was in the neighborhood, I might check out the epitome of materialism. I'd like to visit the mall. I've heard their hot pretzels are...heavenly."

"But the nearest mall is seventy miles from here! How will you get there?"

The old man smiled, a warm, comforting smile. "I'll walk, he replied. "I enjoy the scenery."

Carey thanked him profusely and drove away at last, fighting tears. She actually forgot very little, because she never spoke of the incident to anyone. Over the years she would check the leather purse but a few times. Each time there would be something there.

The railroad investigators would never quite figure out what had happened. Buzz the engineer saw fit to boast about it nevertheless. "Best brakes in the country," he bragged. Although the paint of the engine shroud had been discolored by heat, no other evidence of fire was ever found.

Whenever the gray guardian had taken any kind of action, there had always been a ripple effect. The poacher was a part of this action's ripple. The hapless hunter spoke of it no more than did Carey, and he never forgot what he'd heard or what he had seen. Consequently, the rifle he had left on the ground beneath the redbrush remained there, and it rusted in place. Deer browsed within inches of the weapon, and the grasses quickly covered it.

Two days later, a clean-shaven man, who very much resembled a certain actor, strode solemnly through the front doors of a busy shopping mall. He wore a long gray overcoat and a gray fedora, and he employed a long wooden walking cane. The weathered grayness of the cane had been well-earned over decades of foot travel, the bottom end worn round, the grain of the wood hardened from use. There was business to attend at the pretzel stand.

*****************