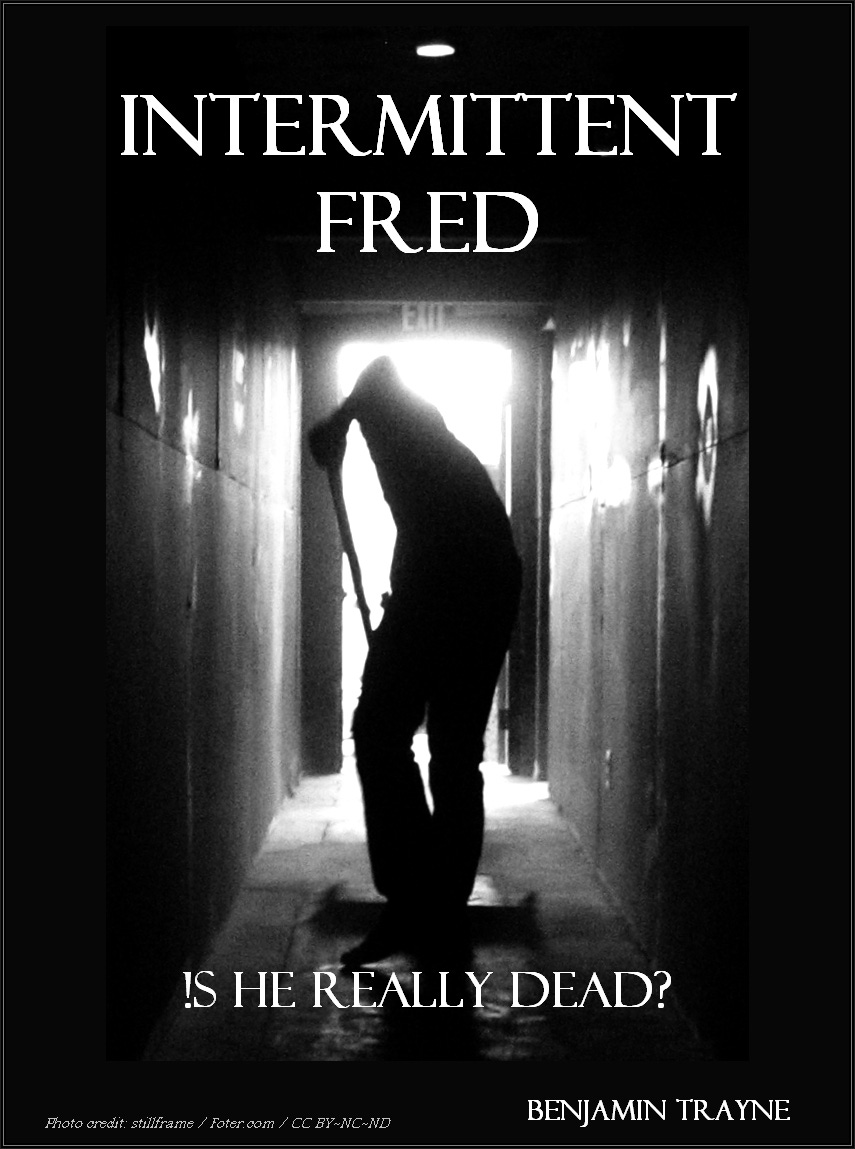

Intermittent Fred. Is he Really Dead?

"There is no doubt fiction makes a better job of the truth." - Doris May Lessing

Intermittent Fred

!s He Really Dead?

Benjamin Trayne

Fred is dead.

He's dead, or so we believe. I have to wonder, I really do, and so do a few others. To appreciate the sentiment, you'll have to know something about the guy.

Fred functioned, sort of, with his mind turned “off”, most of the time. Whenever he came “on”, nobody knew who, or what the hell he was going to be. From a chip-shoveler and broom-pusher to an mathematician, or even a theoretical physicist, who ever knew?

That's because Fred was intermittent. Unintentionally, for sure. Nobody would do this on purpose.

Fred's name wasn't really “Fred” by the way. Since the man has ostensibly entered the afterlife, it's a name I've assigned him out of appropriate respect, to somewhat anonymize him for the purpose of telling this story. For some odd reason, “Fred” is a simple name that I've always liked (and used) so much, that people I know have often called me “Fred”. In fact, a young tomcat showed up at our home last year, and my son remarked, “Dad, Don't name him 'Fred'.” I just looked at him quizzically and posed the obvious question:

“Why?”

Fred is a good cat, as cats go. I mean, if you've gotta have a cat. But I digress. Fear not, this story is not about a damned cat.

You surely already understand, if you're like me, meaning, older than a teenager, nobody's perfect. Fred wasn't either. I saw Fred every day when I worked the daylight trick, as like most of the younger men in the tool and die shop, I rotate through all three shifts.

Fred was our “chip man” at the tool and die. Some people might've considered him a janitor, but a chip man does much more than janitorial work, in fact, the janitorial work was only what he did whenever there was “slack” time from manually shoveling and hauling steel chips. We made a lot of chips, mostly blue and silver spirals and tight little blue “sixes”, which is the shape you get at optimum cutting speeds from carbide-inserted cutting tools. Fred moved up and down the aisles between the machines pushing a big steel wheelbarrow with a heavily worn scoop shovel inside. What he did was hard work. He was clearing away the leavings from the labors of about fifty men, one-hundred and forty if you took into consideration all three shifts. The distance he had to wheel each load to the collection point was about a hundred yards.

And Fred was not a young man. Nevertheless, when he got caught up with the chip piles, he was expected to clean two restrooms, sweep the office areas and carry the trash. Somehow, he always got it done. But for most men, that meant that after a long hard day's work, you went home and got a shower.

Not Fred.

We were never sure why. As Fred was one of the older men there, we didn't harass him about it. The other old guys had given up trying to get him to take a bath, years before. If you asked one of them about it, he would just shake his head. Some theorized Fred's intermittent condition somehow excluded soap and water. Others suggested that Fred's habit cycles were like the orbits of planets. Each planet was something that Fred did. The closer a planet is to the sun, the more often it comes around. The bath planet, then, had to be somewhere out beyond the known universe. For quite some time, we all thought it was the only consistent thing about him. It earned Fred a nickname that I have not changed for the story. They called him “Pigpen”.

Nobody seemed to know much about old Fred, except that he hadn't been born in our area. He just drifted into town and took up residence in a formerly vacant shack near the railroad tracks, about a half mile from our workplace. He'd been working long enough at the tool and die when I arrived that no one seemed to know how he'd come to be employed there, but it really didn't matter. The bosses had set up a system of payment for him that made cash available at the bank. Very likely he never filed taxes, because he didn't seem to have the presence of mind to handle that. But you have to give them credit, they took Fred's obvious shortcomings into account. Once in a while he didn't show up for work, and they let it slide. Other times, we were told, he'd had to be turned away at the gate on a Sunday, because he had shown up. He'd be punching the time clock on his way out on Friday, and the guys would be reminding him, “No work the next two days, Fred.” For the most part, it seemed to work out.

Whatever had taken Fred's mind away hadn't gotten all of it. That's where the truly intermittent part comes in. At irregularly-spaced intervals, like, weeks apart, he'd be bent over, shoveling chips, and he would suddenly stop; he would straighten up, look all around and say, loudly, “What in the hell am I doing here?” It was always that same remark. At that moment, men would stop their machines and walk on over to listen to Fred. I'm sure it was the entertainment factor, because the one thing you did know for sure, was that whoever he was at the moment, it would be a far cry from the day-to-day Fred we all knew.

I honestly wish I'd had a tape recorder, some of the times I'd heard him speak. Fred would stand there and go on about his degrees, because supposedly, he had one in mathematics and another in physics. He sounded convincing, but most of what he had to say, nobody really understood. Maybe he actually did have degrees. The guys would just smile and nod, and listen; because he wouldn't talk about it for more than three minutes or so. Then he'd stop, his eyes would glaze over, and after another minute or two, he'd solemnly go back to work.

To explain why he actually may not have died, I have to explain the rag-ball incident. To understand that, I have to explain our third shift.

Actually, nobody could really explain third, the understatement of the century. I always rotated through the shifts, as I said. I worked a week on daylight, then a week on the three-to-eleven, then a week on third, which was eleven pm to seven am. Young men weren't allowed to work all daylight, you had to have some seniority to get that. But if you were so inclined, you could work all second shift or all third. The hard-core butt-heads worked all third. No supervisor wanted to work overnight, and the company had the poor judgment to let them work without one. So of course, on a very regular basis, all hell broke loose on third shift.

A week before the Fourth of July and a week or two after, it was a good idea to wear earplugs constantly, if you were on third. That was because the favored weapon of choice during those weeks was the venerated M-80. I had one explode so close to my head once that I didn't hear it go off, but rather, felt the concussion. After that I didn't hear much of anything for a month. The earplugs didn't help you, either, to dodge the rockets that often streaked up and down the aisles.

The water battles were epic. Some idiots, I mean workers, ha-ha, would have satisfied themselves with an icewater-balloon lobbed overhand from halfway across the shop onto some poor unsuspecting machinist's back, particularly if he had his nose close to a critical operation on his machine. Not these guys. They got out the fire hoses. It took a while for management to catch on. I think the giveaway was finding Ernie, the smallest guy in the shop, suspended from the ceiling in a harness fashioned from a flaccid canvas water hose when they came in at seven am, and puddles everywhere around on the concrete floor. Ernie just hung there, looking sheepish. He was dripping wet. Strangely, he had no idea what had happened. At least, that's what he told the bosses. It’s what you do, in the interest of self-preservation.

One day we were shooting the breeze as we got ready for the daylight shift, and one of the regulars from third was there, still putting his tools away. Rick was a short guy, cocky and rude. He was describing a large herd of deer that he'd seen near his home, the previous morning. Somebody asked, “Hey Rick, were any of 'em bucks?”

“Nope, but I can't be sure,” he answered. “They all had their backs to me. There was nothin' but assholes, as far as the eye could see.”

“Sounds like third shift!” remarked one of the daylight guys, and the whole place erupted in laughter. It was funny, of course, because it was true.

So of course, in any group of forty or so guys with no supervision, someone, sooner or later, will throw something at someone else. In this case, it started harmlessly enough. Someone knotted up a shop rag, a bit of linen about a foot square, and threw it like a baseball, clocking his target firmly on the side of the head. Such things never go without a response. Before long, no one in the shop on any of the shifts could find a flat rag to wipe the oil or coolant from a finished part. They were all knotted up into rag balls, laying everywhere around the shop. Of course nobody wanted a management inquisition, so nobody called it to their attention. The older, more savvy die-makers simply gathered them up, un-knotted them and hid what they needed for their own use. The rest of us did without. Paper towels vanished from the restrooms.

But of course, machinists are a crafty and inventive lot. So the first improved ragball was a ragball dipped in toolmaker's wax. The stuff is some kind of hot resin that's kept in heated pots. Finished tools are dipped in the stuff, and it hardens at room temperature, protecting the tool until it's needed. This improvement made quite a weapon out of a ragball. Of course, it wasn't enough. Somebody had to weight the weapon, to put some force behind it.

So the ragball Mark III was knotted around a large steel nut. A steel nut is the thing you thread onto a bolt, you know? Fortunately, a shop rag won't knot well around the really large ones, the size that's like, a man's fist. But the heavy-hex, one-inch eight-pitch nuts were just about right. I know this because I rotated through third, and self-defense is necessary. With this bunch of guys, you were either a participant or a target. There is no mercy.

Soon there were no more one-inch heavy hex nuts anywhere in the plant, except of course, in the centers of hundreds of ragballs. Ragballs began to approach technological perfection, as their makers learned to make a heavy, tight, hard-as-a-baseball sphere out of one nut and two surrounding rags. Of course, the completed ragball was then dipped in toolmaker's wax. And it was pretty much a lethal weapon, in the hands of some of these guys. Ribs were cracked, safety glasses were broken, and in short, the whole shift needed to be dumped onto the street without fanfare.

It all came to a head one night when a well-meaning supervisor asked Fred to make up a missed day by working a night of third. I'm sure Fred didn't fully understand why, but of course, he complied. On third shift, however, no respect was shown for anybody at all. Fred would not become the first exception.

The first big ignominy suffered by poor Fred was an overdone dousing with the fire hoses. But the smell was, in fact, offensive, and you didn't offend the third shift regulars as a group without reprisal. They hunt together, fight together and drink together. That's just the way it is.

I wasn't on third that week, or I would have tried to stop it. Of course, I'd have gotten soaked too, but Fred didn't deserve that, no matter what. On the plus side, he probably forgot about it quickly. On the minus side, it wasn't over.

From what I understand, Fred took the soaking like a man, and probably he and his duds came out the other side of it a couple of pounds lighter. I'm told he simply went back to work.

I was also told that the strike to the head with a ragball was an accident. That's entirely possible. Ragballs were like the Fourth of July rockets; they were everywhere, unannounced and really tough to avoid. Supposedly, at the very moment big Ed whaled one at Rex, Fred, who had been bent over pushing the scoop shovel, stood up.

Ed could have pitched major league baseball, and Rex was big enough to take the hit. It would take something to break those ribs, because they were well-protected with muscle. Fred's cranium, however, was not.

He had made it through almost all of the shift, and a few of the daylight guys had already filtered in, me among them. Also among us was a trained paramedic, we'll call him Charlie, who probably should have become a doctor. He was excellent. Of course, he was called over immediately, because Fred was out cold.

Charlie called 911 and then attempted CPR, but after a few minutes, he pronounced Fred dead. There was no pulse, and Fred wasn't breathing. Charlie knew third shift, and he knew that under innocent circumstances, they wouldn't have cared at all. But they were all standing around, looking sheepish and worried.

“Awright,” Charlie demanded, “Who the hell did this? What the hell happened?”

Maybe I shouldn't have been surprised when Ed stepped forward. “It was an accident,” he said, with uncharacteristic softness. “I didn't mean...”

“Shut up and get a litter,” Charlie snarled. “The man is dead. Not leaving him here in the middle of the shop.”

Big Ed didn't listen. He carefully gathered up Fred's body and carried him like a big baby, straight into the office, where someone cleared off a desk with a sweep of an arm. In retrospect, I don't know why they put him there. None of the workbenches were large enough, I guess that's why. A blanket was placed over him. Then, a crowd of arguing miscreants gathered outside the office. More men were arriving for the day shift, and everybody was getting into it.

I should mention that everyone was congregated in front of the office, which was quite large. It had three doors, including one at each end.

About fifteen minutes after I got there, paramedics from the local firehouse arrived, the ambulance, immediately after that. Bob, the lead supervisor, advised them that the man they had come to help had expired.

“Well then, where's the body?” I've always been underwhelmed by the delicacy of some of these guys. Bob led the way, but lo and behold, Fred wasn't on the desk. Fred wasn't anywhere. A shop-wide search by ninety men from two shifts ended when Fred stepped out of a restroom carrying three full bags of trash.

The short version, Fred was taken to the hospital, admitted for observation, and cleaned up somewhat by some stoic nurses. They released him the next day after deciding there was no physiological reason to keep him. Bob told a doctor there that Fred probably should be examined by a neurologist, because there had to be something else wrong with him...since before the accident, that is.

“Sir,” the doctor replied, “We have no reason to keep him. You can't treat stupid.”

At least, that ended the era of ragballs.

But the rest of this story gets a lot weirder. I personally think it was connected in some way to the ragball incident, but I have no proof. It's just a feeling.

Several more months passed. When Fred didn't show up for work for two days, on a Thursday, supervisor Bob visited Fred's shack to see what was up. This time, Bob said, Fred was really dead. The odd thing was, he was fully dressed in an expensive-looking gray suit, was clean-shaven and his hair had been cut and combed.

The standing joke after that, and I'm sure it originated from third shift, was that “Pigpen” had taken a bath, and it had killed him.

None of us got to see Fred's body, but I'm told that fourteen of us, including myself, visited the mortuary to advise that Fred might not actually be dead.

“Oh, he's dead alright,” the attendant said. “Relax. The coroner checked carefully.”

We may have a respectable, surviving industry in our town, but it's still a one-horse town. The county coroner isn't even a doctor.

That night, I had a nightmare. Fred showed up at my front door, globs of clay sticking to his forehead, and he spoke, in a hollow voice; “I'm not dead.” I woke up, screaming. Fred didn't know where I lived, so I'm not sure how my subconscious conjured that up.

But the really difficult part came after the simple funeral service. I was told that since no one had access to Fred's bank account, which we later learned had over a hundred thousand dollars in it, Fred received a pauper's burial in a pine coffin, with no vault and without embalming. I didn't even know that was legal. Turns out, people sometimes actually ask for that. It's called a “green burial.”

Half a dozen of his co-workers gathered around the fresh grave with a simple marker, and the preacher read a passage. Then he said, “Fred was a simple man. He was alone.” That ended the service.

Later that same night, a Saturday, a bunch of the third shift guys were drinking together at a local bar, as was their habit.. They all got pretty smashed. As was their habit. I'm told they decided to go and dig Fred up, to make sure he was really dead. Knowing these guys, I definitely could imagine that happening.

The story I heard Monday morning was that they actually got a shovel and went there. But when they arrived, they found the ground had been more than a little disturbed, already. The formerly mounded, dry earth had become a receding dimple. That sobered them up to a degree, and they say, they simply got the hell out of the cemetery.

Well, I decided to check. As soon as I got off at three, I walked to the cemetery instead of to the parking lot. But if anything had been disturbed before, it wasn't anymore. If there was any truth to the story at all, then someone had fixed things up. It looked to me, exactly as it should.

Three weeks later, I was again working the daylight shift. I'd heard that the state would be taking the contents of Fred's bank account, that no living relatives had been found. I finished up my work day, went home, fed the pooch, got a shower and sat down in front of the television with my dinner, to watch the news. We have a satellite dish, and I'd just happened to hit a local news channel from Chicago, a thousand miles distant.

They ran a piece about a long-lost professor who had at last resurfaced. He claimed he'd been abducted by aliens who had forced him into slavery. The guy's children, apparently in their late thirties to early forties, were gathered happily around him, a daughter holding onto each arm and a son standing proudly behind him. He was smiling broadly, and was wearing a gray suit.

I'd never seen Fred clean, or without a shaggy beard or long hair. But if I had, I think, he would have looked just like that guy. I thought to myself, I don't have time for this.

I'm not saying a word.

*******************

copyright 2023